October 2022 is National ADHD Awareness Month. Now, more than ever, is a good time to reflect on “neuro-diversity”. That is- the brain differences that exist in us all (versus a “one-brain fits all” approach). It can be helpful to know a bit about disorders like ADHD without feeling the pressure of being a scholarly expert in doing so. I hope to achieve that with the information below.

Let’s start with some facts. In a “nutshell” Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is the name of a Neuro-Developmental Disorder that can be found in the Diagnostic Manual for Mental Health Disorders (DSM-5-TR). There are three types named: Hyperactive, Inattentive, and Combined type. Individuals who have been diagnosed with ADHD experience a wide variety of symptoms (twelve listed in diagnostic criteria between types) that present similarly to other mental health conditions such as anxiety or trauma-stressor related disorders. Persistent symptoms typically emerge in childhood development and can include things like difficulty concentrating, hyperactivity, forgetfulness, impulsivity, and losing interest in tasks quickly that require big mental effort.

These hallmark symptoms of ADHD impact daily functioning and can present differently in girls and boys. The executive functioning domain of the brain, sometimes referred to as the “thinking brain”, is wired differently in the ADHD brain making it difficult to concentrate, make decisions, rationalize, think before doing, relate to others in a social context and “listen or behave” as expected by their social counterparts. It is a disorder that can be over-diagnosed or misdiagnosed without a full psychological evaluation or thoughtful consideration of the child’s trauma history, which can also rewire a person’s brain and alter external behaviors.

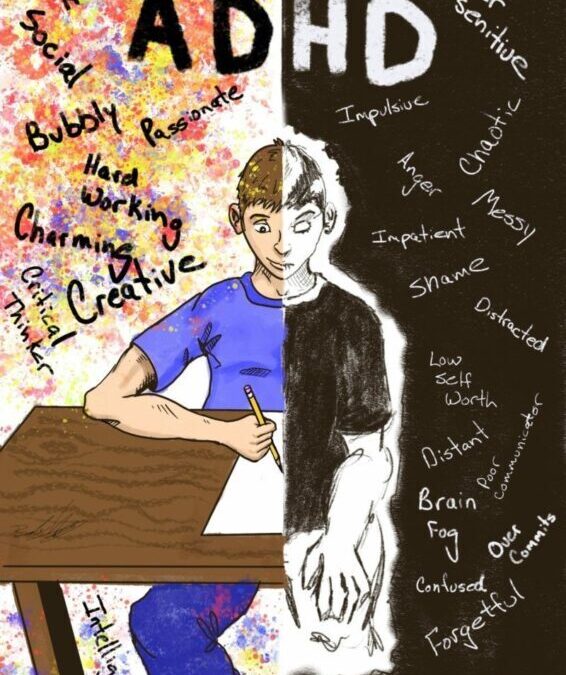

This all sounds…well, hard… doesn’t it? It sounds like it would challenging to experience the world in a brain and body that feels uncontrollably busy, feels pulled in any direction, and never stops. Though, more often I hear about a different kind of struggle. The challenge of living in a social environment that can stigmatize, dismiss, or punish behaviors that go along with a biological condition such as ADHD and which can lead to isolation or adverse experiences.

Think about a time where you have heard or experienced a “disruptive kid” in school or another setting. Is this the kid who seems to be not listening/ignoring you? Is it the student that constantly forgets things? Is it the kid who is not able to stop talking or impulsively blurts things out or otherwise? A lot may be happening underneath the behavior. A good place to start is reflection. Ask yourself, “What could be happening internally-with brain and body?” This is a great way to begin understanding not only ADHD, but with things like trauma, stressors, and anxiety, which can present similarly though require different assessment and treatment.

As a mental health therapist, I have seen children who are expected to perform beyond their natural born abilities but simply can’t and then begin to internalize a messages of, “I’m stupid” or “I’m different and different equals bad”. Unfortunately, for some this message is reinforced further when adults scold, reprimand, or point out their differences as deficits. As caretakers of our children and their emotional development, what would it be like if we could see beyond their behaviors? What if we used a strengths-based approach when interacting with children diagnosed with ADHD? There are many and included strong links to creativity, the ability to actually “hyper-focus” or utilize energy towards a particular interest in the fullest capacity, or athleticism.

De-bunking myths and sorting out the facts leads to the “ah-ha” moments to make meaning out of our experiences. Also, this: the brain has the ability to change (called neuro-plasticity) and there is still so much to learn about the capabilities of the brain and how treatment can be effective or otherwise. A diagnosis is not a lifelong sentence for struggle of “you’re not like the others.” A diagnosis such as ADHD is just a set of criteria that informs treatment. A diagnosis should not define a whole person or become an identity or identifier for an individual.

It may be helpful to explore some of the common myths about ADHD as seen below. These were produced by the ADHD Awareness Month website (https://www.adhdawarenessmonth.org/):

MYTH: ADHD doesn’t exist

FACT: There are more than 100,000 articles in science journals on ADHD and references to it in medical textbooks going back to 1775.

MYTH: People with ADHD just can’t concentrate

FACT: Individuals with ADHD can concentrate when they are interested in or intrigued by what they are doing.

MYTH: ADHD is caused by bad parenting

FACT: Brain-imaging studies show that differences in brain structure and wiring cause problems with attention, impulse control and motivation.

MYTH: All children grow out of ADHD

FACT: Significant symptoms and impairments persist in 50-86% of people with ADHD.

MYTH: ADHD is just an excuse for laziness

FACT: ADHD is really a problem with the chemical dynamics of the brain and it’s not under voluntary control.

MYTH: Children with ADHD just need more discipline

FACT: Discipline and relationship problems are the consequences of ADHD behavior problems in the children, not the cause.

When working with families, I have seen it helpful to provide information about cognitions and feelings (internal) and behaviors (external). Adults at any education level benefit from understanding the relationship between what is seen and unseen, so they can respond, communicate, and lift-up a child who may experiencing an internal struggle, whatever struggle that may be. When we exercise understanding we are offering trust and support that fosters growth.

For those who are experiencing symptoms of ADHD, it is recommended to find evidence-based resources to learn about it. Another option is to contact a mental health clinical professional who has specialized training, understands new research, information, and treatment of mental health disorders. This is not to say a primary-care or general practitioner are not good resources. It’s a matter of “scope of practice” in which professionals stay in their lane of expertise and seek out the perspectives of allies in specialized areas. Ideally, a collaborative relationship between a medical doctor and mental health professional is appropriate as research has established mental health and physical health are undeniably related.

If reading scholarly journals or digging into research aren’t your thing, you can learn more about ADHD through quick and easier-to-digest facts from the nonprofit agency: Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (CHADD- https://chadd.org). Here you can find resources specifically offered for this month’s ADHD Awareness Month, as well as support for children, caregivers, and teachers. I also recommend ADHD-centered documentaries such as “The Disruptors” (https://disruptorsfilm.com/adhd-resources), to learn about perspectives from mainstream role-models who’ve experienced both strengths and challenges of ADHD.

Below are a few additional resources that I have found to be helpful for caregivers, educators, and children:

CHADD (CHILDREN AND ADULTS WITH ATTENTION DEFICIT DISORDER)

AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION (APA)

Child Mind Institute

CENTER FOR PARENT INFORMATION AND RESOURCES (CPIR)

UNDERSTOOD

COUNCIL FOR LEARNING DISABILITIES

Written by:

Lea Morey Finstrom, MA

Individual and Family Therapist

Lakes Center for Youth and Families

Recent Comments